“A Voice for the Voiceless”.

This is how Shaun Tan describes his picturebooks, and more particularly The Arrival in his article for the October 2011 edition of Bookbird “The Accidental Graphic Novelist” ( you can also access it for free here, and I urge you to read it).

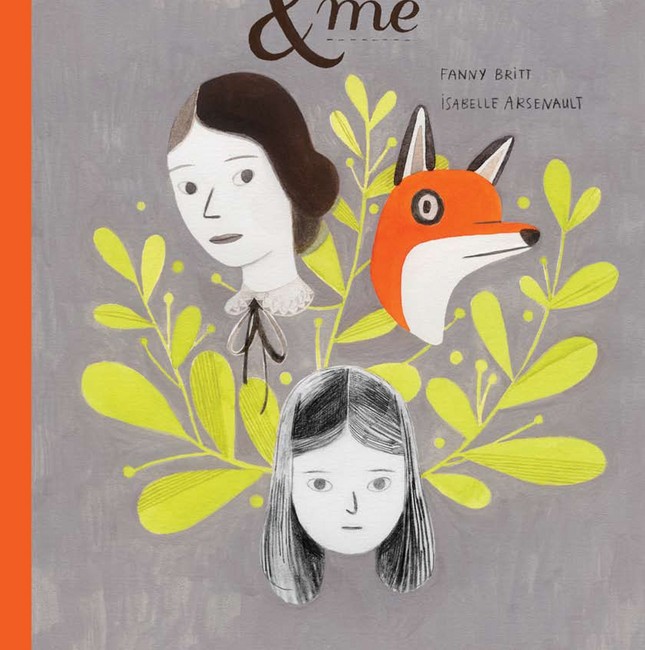

He continues by saying that graphic novelists (citing artists such as Craig Thompson, Joe Sacco, Alison Bechdel, and Mariko & Jillian Tamaki) often focus, like him, on characters who have “problems expressing themselves, from troubled young people to persecuted minorities and those suffering from emotional, intellectual, or spiritual obstructions”. For Tan, the graphic novel is the perfect vehicle for those unspoken feelings. Adding the wordless element to such a format allows the story, again according to Tan, to convey something to allow it to “be devoid of comment, prejudice, or political noise. Like a tree, a cloud, or a shadow, the drawings just are“. He continues later by adding that wordless graphic novels seem the perfect vehicle for ideas which seem so unfamiliar, that they can only be told through “a visual subversion of words”.

One can see how The Arrival fits into this – a story is about the unfamiliar, about feeling alienated and alone. A story that is universal nonetheless.

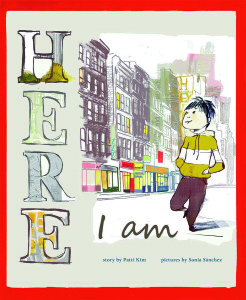

Here I Am, a wordless picturebook told in a format which is predominantly inspired from graphic novels, by Patti Kim (story) & Sonia Sánchez (pictures) and published by Curious Fox illustrates very pertinently how such a format can give a voice for the voiceless, in the same way that The Arrival does. It tells the story of a boy and his family, newly arrived from their faraway homeland to New York, as they try to adjust to their new life and attempt to fit in. It is visually stunning, and works beautifully at conveying not only the feelings of alienation and isolation which come with being an immigrant, not comprehending the language of a new land, but also the wonderment of finding oneself in a new place. Without words to distract, readers pay more attention to the artwork and the story they tell: the body language of the boy (full of sadness and tense at first, then relaxing), his surrounding, and the little things that he notices along the way. This is where the smart use of panels really comes into its own, highlighting details which might seem inconsequential to the narrative but in fact are vital to the boy’s story and eventual happiness in his new surroundings. The artwork might seem over-crowded at first, but it all comes together beautifully to create the right atmosphere: the hustle and bustle of New York streets, the attack on the senses that a new world with new smells, new surroundings bring.

Here I Am, a wordless picturebook told in a format which is predominantly inspired from graphic novels, by Patti Kim (story) & Sonia Sánchez (pictures) and published by Curious Fox illustrates very pertinently how such a format can give a voice for the voiceless, in the same way that The Arrival does. It tells the story of a boy and his family, newly arrived from their faraway homeland to New York, as they try to adjust to their new life and attempt to fit in. It is visually stunning, and works beautifully at conveying not only the feelings of alienation and isolation which come with being an immigrant, not comprehending the language of a new land, but also the wonderment of finding oneself in a new place. Without words to distract, readers pay more attention to the artwork and the story they tell: the body language of the boy (full of sadness and tense at first, then relaxing), his surrounding, and the little things that he notices along the way. This is where the smart use of panels really comes into its own, highlighting details which might seem inconsequential to the narrative but in fact are vital to the boy’s story and eventual happiness in his new surroundings. The artwork might seem over-crowded at first, but it all comes together beautifully to create the right atmosphere: the hustle and bustle of New York streets, the attack on the senses that a new world with new smells, new surroundings bring.

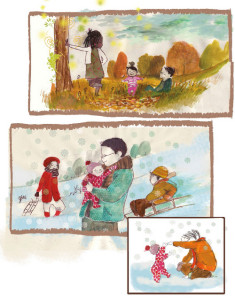

And finally, as friendship blossoms and a happiness and contentment creep in, it is interesting to see how the colour scheme but also the panels convey that: the panels merging to seal the friendship, their sudden lightness, like little snapshots of happiness and the final, frameless, illustration, full of acceptance and hope. It all comes together so beautifully.

The format does not only allow the reader the time to notice these details, but it also guides the reader: the use of panels ‘force’ the focus on certain details of the story; yet the reader is still able to bring his own experience and emotions because of the lack of words. This creative process, where picturebook creator and reader find themselves accomplices (or partners in crime as Scott McCloud puts it) is what gives the voiceless their voice. In the case of Here Am I, in those final spreads, I can almost here the boy humming.

Lovely post Melanie. Another thing that interests me about this book in its borderland between picture book and graphic novel is the style of the art. Without having the technical language to describe it, I would say it looks much more like picture book than graphic novel, because of the varied textures and shadings, the way the people are drawn. I like that it pushes the boundaries of what I typically think of as a graphic novel.

That is kind of what Tan talks about in his article – he never set out to create a graphic novel with The Arrival. It was just the right format for the particular story. There is definitely a blur of the boundaries, in fact some people like Philip Nel consider picturebooks and comic/graphic novel to be of the same genre, with the form differing. When I wrote my essay I called this specific sub-genre “wordless graphic picturebook” – bit of a mouthful but it recognises the two aspects: it is a picturebook with a comics/graphic novel format. what identifies them is often, you are right, that the style of the artwork itself might be more “picturebook-like”.

Looks wonderful!

Thanks for helping me understand WHY I loved the “look” of the books in Part 1 and 2, but didn’t have the precise words to explain until you put it so clearly, Melanie.

I am glad to be of help 🙂

I am doing an MA in Children’s Literature and I’ve just written an essay of wordless picturebooks that use graphic elements (though not those particular books) so wanted to write these ocuple of posts while it was still fresh in my mind 🙂