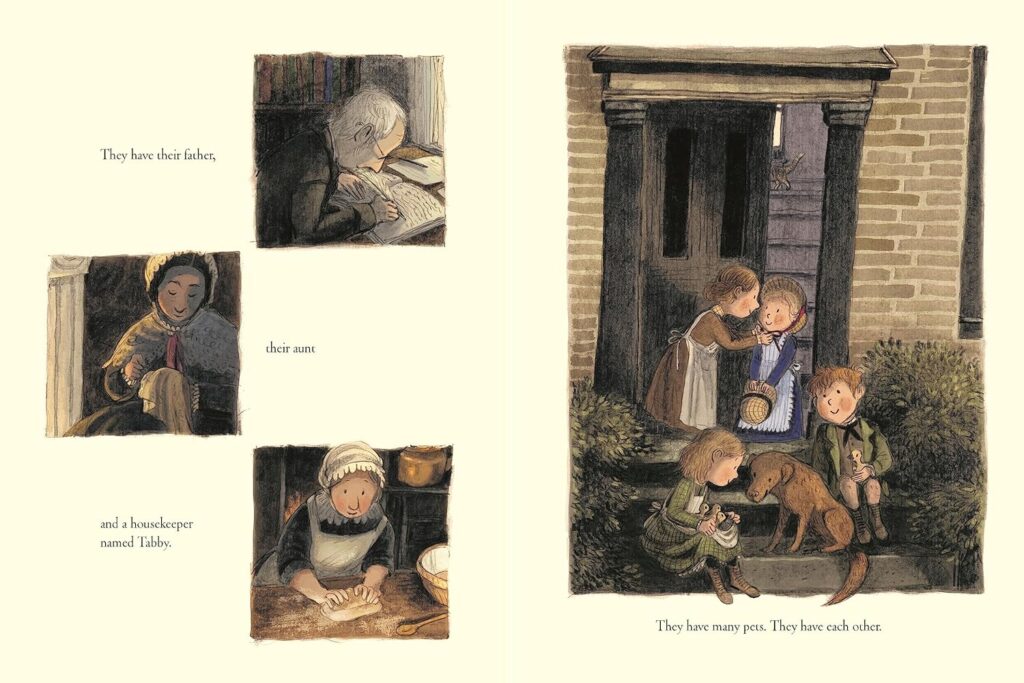

The Little Books of the Little Brontës, written by Sara O’Leary and illustrated by Briony May Smith (Walker Books), focuses on the childhood of the four Brontë siblings and their rich creative lives, firstly painting and writing stories in little books, then later world-building the paracosmic Glass Town, based on a group of toy soldiers gifted to Branwell by their father.1 The book mixes this with a glimpse of their every day life both inside of their home where sorrow and joy cohabit daily and outside in their little town of Haworth and the surrounding moors. This is mirrored in the variety of layouts, alternating throughout the narrative: vignettes, boxed illustrations and full bleed single and double spreads help pace and focus the story.

Sara O’Leary’s gentle prose has a conversational tone which draws the reader right in, even addressing them directly from the very first page and also a candid but compassionate approach to the darker episodes of the siblings’ lives. This approach is mirrored by Briony May Smith’s mixed media illustrations which are warm and soft while never compromising reflecting the austere existence the children led.

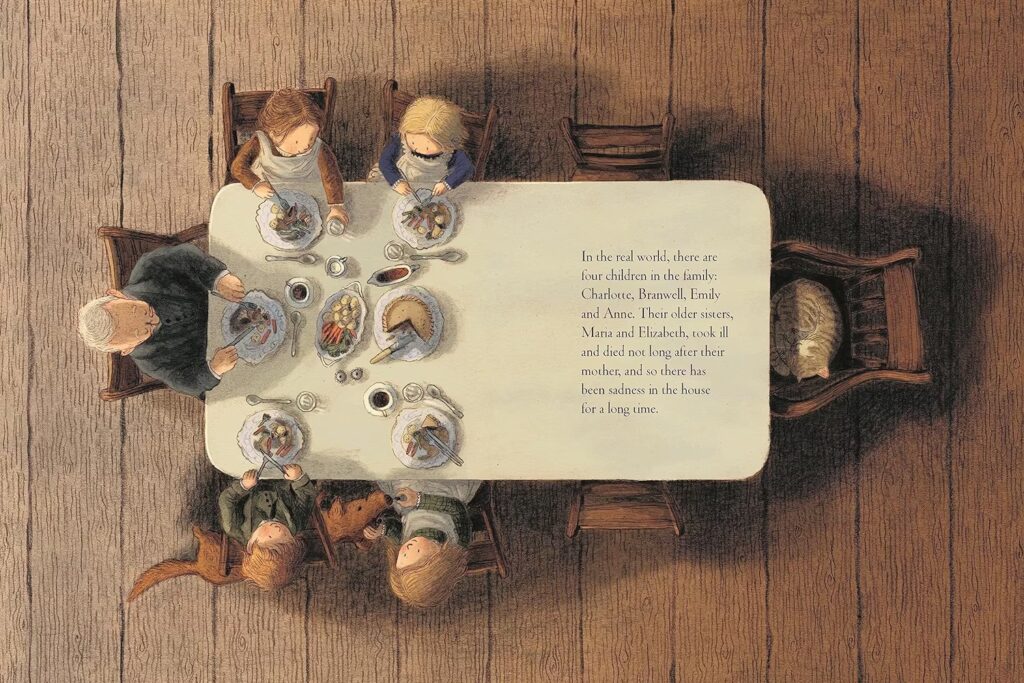

Nowhere is the perfection fusion between words and art more effective in this book than in the dinner scene at the beginning of the book.

This full-bleed double-spread is simply breathtaking. I have raved about it a lot in different places because to me, it is one the most perfect double-spreads I have ever come across; its layout, its composition, the text and its placement, it all comes together so perfectly. In picturebooks, full-bleed double-spreads are often used as a way to make the reader pause and take note; as Megan Dowd Lambert puts it so well, “it’s as though the picture is taking a long time (taking up a lot of space) to say what it needs to say”2 . And in this double-spread, it is as much about the unsaid that about what it is said that makes it so incredibly effective.

Point of view, or the positioning the reader in relation to the picture, affects the meaning we take from the illustration. If given the point of view of a character within the story, we see the world as they do, from the same vantage point, which might narrow our perspective and understanding. If given a bird’s eye view of a scene, we are privy to a whole scene, without any interference; however as David Lewis suggests, our perspective is nonetheless manipulated, by the artist, who chooses this view point “to make us see things in a particular way, to ‘subject’ us to the order of things as represented”3.

The entry point the reader is given here is so important to understand the family dynamics in the Brontë household at the time of the story – a loving family on the left (position of safety) enjoying a meal, obviously chatting. But on the right, a position of uncertainty, the table is left bare apart from the tablecloth, with three empty chairs representing the missing family members (the mother and two older sisters). The cat sitting on what we assume to have been the mother’s seat and the large shadow surrounding the chair4 cleverly conveying both the void of her absence but also her transcendent presence. The positioning of the text both explains and somehow fills the empty space left by the departed. It is a deceptively simple, multi-layered with meaning in a way that only picturebooks and the interplay between text and image can create and convey.

This double-spread is so moving, so impactful, I really wanted to find out how it came to be. Authors and illustrators more often than not do not confer during the creative process, and I was interested to find out their individual takes on that particular spread.

Sara O’Leary, author:

This image of the little Brontës sitting at the table with their father and the three empty chairs representing their mother and two sisters is incredibly moving to me. The first time I saw it, the breath caught in my throat and I made a noise like someone had hit me in the chest with a heavy object. Because that is precisely what happened!

This was a difficult book to pitch. There were concerns that the subject matter was too dark and that the lives of the young Brontës were too full of suffering to provide suitable material for a book for young people. Their mother died when Anne (the youngest) was only one. Charlotte was five and retained only vague memories of her mother who had been ill for some time. After that loss, the two elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth were sent away to school and then brought home again, dying of tuberculosis. They were twelve and eleven. These losses would not have been at all unusual for the period but in the contemporary imagination they mark the Brontës out as tragic figures.

In this single spread of the remaining Brontës seated around the dining table, Briony captured everything I hoped for with the story. The tragedy is there, yes. Those absences have a weight and a presence that is inescapable, but we also are shown warmth and reassurance and a family that goes on. There’s a line later in the book to the effect of “they had each other” and that’s what we see in this spread.

The dining table is conspicuously empty at one end, but at the other there is companionship, warmth and engagement. There is more than enough food for all. And the characters are so engagingly drawn, that you can almost hear the chatter of Charlotte and Anne on one side of the table and Branwell and Emily on the other. In later years, the dining table became an important locus for the sisters. In the evenings they would walk in circles around the table, reading and discussing their writing and their plans, and in her final years, Charlotte was left to pace around the table in solitude, unable to sleep without enacting the ritual performed with her sisters. But here the table is where the family gathers.

Throughout the book, we see the presence of animals, so important to the Brontës and to Emily in particular. Here they are particularly significant as they help to fill the empty spaces. There is a cat contentedly curled up in what would have been the mother’s chair and a dog on the floor below the table. Emily used to get in trouble for feeding her meat to the dog and that is exactly what she is shown doing here.

And where are we in this picture? As readers, we have been suddenly given a God’s eye view of the family. This is a term that comes from filmmaking, not the picture book arts, but it is more than apt here. It’s a technique beloved by Hitchcock, as is another that we see in the first spread of the story where we enter into the action through the window of a building as though we are eavesdropping on a conversation. Both are used to effect here.

Briony’s work is often justly praised for the appeal of her characters and for the beauty of her landscapes. But in a spread like this one we also see that she is operating on a very sophisticated level conceptually. She is making choices that will affect the reader on a subliminal level–it’s impossible to make the page turn to this God’s eye view spread without subconsciously realizing so much more about the characters than can be put into words.

This spread provides the background to the story which really opens with the creation of the first of the small books created by the children. There are just 44 words on this page. One of the ones I remember insisting on was “died” because I wanted to talk about the losses the family had suffered without resorting to euphemisms. The book focuses on the creativity of the little Brontës, but I didn’t want to shy away from the immediate experience of mortality those children had.

We have no images of the Brontë sisters as children and only a few of them as adults. Briony colour-coded the garments worn by the children so that they correspond to the colours the sisters wore in the portrait of them painted by Branwell. We talked about things like what garments they might have owned, how they would have worn their hair, and when Charlotte would have started using spectacles. And I find Briony’s depictions of them quite believable as well as being totally endearing.

You ask what I pictured for this spread when I wrote it and I’d like to say it was this, but I’m not sure I pictured anything at all!

The text is about loss but the image needed to find a way to balance that–to provide the warmth and reassurance a young reader might need. And Briony found a way to convey that. This is why the collaborative nature of making picture books so appeals to me.

I have a line in another book where a child asks their parents, “Do one and one make always two, and never something more?” For me–at their best–picture books are a medium where a writer and an artist can make something more than either of them could’ve done alone. And if I was asked to illustrate this ideal of collaboration, I would point to this utterly brilliant spread from Briony.

Briony May Smith, illustrator:

Sara explains the deaths of their sisters and their mother without any euphemism, which I really love: it trusts the reader with the tragic facts of their young lives. But in her beautiful writing, Sara gives ‘sadness’ a presence of its own in these pages, right at the moment of introducing the whole family. The story wanted a family scene in these pages, which at the same time expressed who was missing. The three empty chairs, the balance of it against the left side of the table, and the empty space on the tablecloth itself for the type, seemed like a good approach for these haunting words. Sadness sits to the right, and the family to the left. But it’s ultimately a family scene, and an introduction to the living in the house, and so I hope their familial interactions and the animals they are surrounded by add a lightness, too.

Thank you so much to Sara and Briony for the wonderful insight!

Source: Review copy kindly provided by the publisher

The Little Books of the Little Brontës is available now to buy from all good bookshops or can be purchased via our partner bookshop, Storytellers, Inc.:

Footnotes

- I thoroughly recommend the graphic novel Glass Town by Isabel Greenberg (Jonathan Cape) for another interpretation of the Brontë siblings’ creative genius. ↩︎

- Reading Picture Books with Children by Megan Dowd Lambert (Charlesbridge), p.53 ↩︎

- Reading Contemporary Picturebooks: Picturing Text by David Lewis (Routledge), p.159 ↩︎

- This reminded me of Nanny McPhee bowing to the mother’s chair as if she is still sitting there in the movie ↩︎