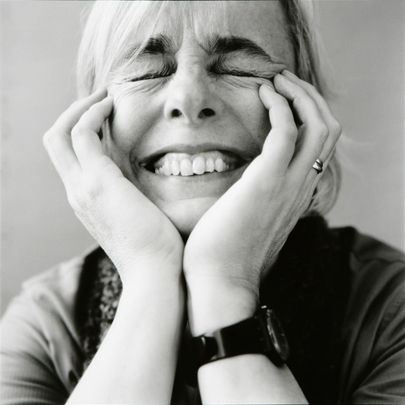

Today is a really special day because I get to present a guest post from one of the YA authors I admire the most, Margo Lanagan. I don’t really “do” fantasy usually but the worlds that Margo creates in her writing are like no others. Her stories are fascinating, yet leaves readers almost breathless so evocative is her writing, and always, always utterly compelling. I discovered her work when Tender Morsels was published. In fact it is another of my favourite authors, Meg Rosoff, who is responsible for this as during a speech at the 2009 Federation of Children’s book Groups. she talked about Tender Morsels with such passion that I felt compelled to seek it out. I was not disappointed (see my review here), and neither was I by Brides of Rollrock Island which was one of my highlights in 2012 (see here). However Margo Lanagan is also an acclaimed writer of short stories and as her latest collection, Yellowcake, was recently published (see my review here) I asked her if she would talk about her experience of writing in both formats.

Today is a really special day because I get to present a guest post from one of the YA authors I admire the most, Margo Lanagan. I don’t really “do” fantasy usually but the worlds that Margo creates in her writing are like no others. Her stories are fascinating, yet leaves readers almost breathless so evocative is her writing, and always, always utterly compelling. I discovered her work when Tender Morsels was published. In fact it is another of my favourite authors, Meg Rosoff, who is responsible for this as during a speech at the 2009 Federation of Children’s book Groups. she talked about Tender Morsels with such passion that I felt compelled to seek it out. I was not disappointed (see my review here), and neither was I by Brides of Rollrock Island which was one of my highlights in 2012 (see here). However Margo Lanagan is also an acclaimed writer of short stories and as her latest collection, Yellowcake, was recently published (see my review here) I asked her if she would talk about her experience of writing in both formats.

****

The Short and the Long of Short Stories

by Margo Lanagan

I write both short stories and novels, for different reasons. I’m usually working on a novel, and short stories happen alongside that larger operation, as a break from it and as a way of remaining visible as a writer in between books.

When you write stories, you get into the habit of picking up ideas, of noting things down. You end up with notebooks full of possibilities, and this can produce a kind of panic, that life isn’t long enough for you to use up all these great ideas. It’s true, life isn’t—but being a short story writer means that you get to use up more than you would writing only novels. You get to play with more toys; you get to live more lives inside more characters; you get to rule the world in a greater variety of ways.

Short stories, for me, involve less angst than novels (for some writers, the reverse is the case). Some short stories I can draft in a couple of days; I’ll write up to just before the climax one day, and treat myself to the climax and resolution the next. I feel a lot freer with a short story idea than with a novel idea. I can have a few stabs at it, if it doesn’t work. I can start from scratch and it doesn’t mean I’m throwing away three months’ work. It doesn’t require so much heavy lifting, psychologically.

Short stories, bless them, are short. I can see all of a short story at once—all its events and characters, all its flaws, doubts and fuzzy bits. When, three-quarters of the way through, I decide that the voice must be not like this but like that, or that I must tell it from a different point of view, or give it a completely different atmosphere or outcome, it takes me days to pull the rest of the story into line, instead of weeks. It’s easy to lop off a limb that’s not working, with a short; I’m surer of my overall plan and I know I won’t use that plot thread later, because I can see all the way to the end.

I also like short stories’ intensity. You have to make the language work really hard; you have to make each phrase function in several different ways, deliver information about setting and character and plot all at once—all without making it seem overworked or precious. When I read a short story, I like to realise at the end how much information the author sneaked into my mind; I like to feel compelled to re-read and work out exactly how she constructed the thing. When I’m writing, I’m not thinking about the audience and about how cunning I’m being, but I’m always working very carefully on the line between economically laying down clues and getting too cryptic for the story’s good. The first draft of a story (that two-day sprint kind of story) is often very cryptic, it’s often written so concentratedly that it amounts to a kind of code, a secret message to myself about how I want this story to be. Other stories come about the other way, rambling around trying to find themselves, needing to be put away and left alone for a while, so that they can grow as they need, by themselves.

Short stories generally involve less fear; they don’t require the extended balancing act that novels do. I’m not saying that a short can’t plumb the depths, but it’s more straightforward in the way that it accesses emotional truths—a novel employs more complex machinery, and performs its digging more subtly. A novel also requires me to employ more devious fear-management techniques, to break down the job into more manageable chunks, to pretend more strenuously that I know what I’m doing, or that I don’t care whether it ends up working or not. A short story already is a manageable chunk, and it usually doesn’t take much effort to really know what I’m doing, to not have to pretend.

I think I’ll always write both forms; sometimes an idea asks for the short, sharp shock of a short story, and sometimes it announces itself as a big, baggy indeterminate thing, a series of questions that requires more lengthy prodding and poking. I want both kinds of animal in my life.

****

Thank you so much, Margo.

The wonderful portrait of Margo Lanagan was taken by Andrew Cook during the Sydney Writers Festival in 2011 (see here)

I haven’t read anything by Lanagan, but I shall rectify this now!