Three girls. A summer holiday. One epic road-trip. And sausages.

Three girls. A summer holiday. One epic road-trip. And sausages.

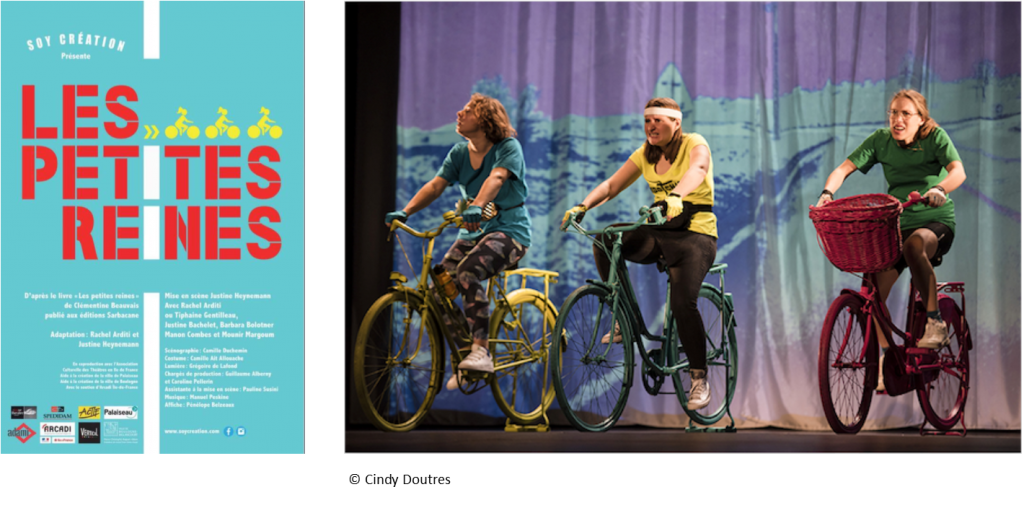

Piglettes (Pushkin Press) follows Mireille, Astrid and Hakima as they embark on a trip of a lifetime to reach, by bicycle, the Palais de l’Elysée on 14th July from their home in Bourg-en-Bresse. All have different motives for getting there, but they share the same motivation for leaving their town behind – they have just been voted the ugliest girls in their school in a Facebook poll. Aided by Hakima’s disabled war veteran brother, they stop along the way to sell sausages (which might seem random, but boudin in French is a type of sausage as well a term to describe an ugly girl). But can they really leave all their troubles behind?

I first read this book in French when it first came out, and I won’t lie, its inherent Frenchness (in the best possible way) had me thinking that this would make it difficult to transfer to another language and culture, but how wrong was I! Clémentine Beauvais translated the text herself, an unusual move in the literary world, and her knowing all the intricacies of her original text of course as well as being accustomed to the target culture , as a long term resident of the UK might have possibly helped her strike the right balance. Whatever her secret recipe is, the subtlety of language, the witty repartee, the clever play on words that made reading Les Petites Reines sheer joy is equally woven into the pages of this English translation.

Mireille’s voice, as narrator, is full of wit; her retorts are crisp and she is fierce, sharp and very, VERY funny. Yet her candour when describing the vitriolic name-calling, the unbearable cruelty she faces from Malo is so frank, it is sometimes hard to read. While she refuses to see herself as a victim, the astute reader will notice what really is going on behind the protective facade built by this utterly magnificent character. It would be unfair however to reduce Piglettes simply to a book about cyber-bullying, While this works as the fuel for the adventure, Piglettes is first and foremost a wondrous celebration of being a girl, and of female friendship; it explores themes of identity, body image, family in all its forms, with a good pinch of social and political discourse too. It is a wonderfully life-affirming read, which will leave its readers elated and is in turns thought-provoking, moving, inspirational and great fun. Teenagers deserve books like these; books that entertain them, but also treat them as the bright, discerning and often opinionated beings that they are. I think, without wanting to sound too patriotic, this is something French YA literature is very good at, and Piglettes is a truly stellar example of this. I sincerely hope this is only the beginning a long overdue French invasion of the UK YA market!

Here is Clémentine reading from the first chapter:

I am delighted to welcome Clémentine to Library Mice to answer a few questions about Piglettes, translation, and French YA.

Hi Clémentine, many thanks for agreeing to answer a few questions about Piglettes! Firstly, Can you tell us more about how it first came to life?

I’d written two grim, sad YA books and I wanted to write something funnier and sunnier. I also wanted to write something that didn’t take place in Paris, for a change. I can’t remember when exactly I had the first idea for it, but it all started from the idea of three girls who’ve won an ugliness contest with a pig-related pun (boudin, in French, meaning both black pudding and ugly girl) and do a road-trip, selling said black pudding. And then I worked on the rest of the story…

I’d written two grim, sad YA books and I wanted to write something funnier and sunnier. I also wanted to write something that didn’t take place in Paris, for a change. I can’t remember when exactly I had the first idea for it, but it all started from the idea of three girls who’ve won an ugliness contest with a pig-related pun (boudin, in French, meaning both black pudding and ugly girl) and do a road-trip, selling said black pudding. And then I worked on the rest of the story…

You have taken the very unusual step to translate your own work. You also translated One by Sarah Crossan into French so have experience of both. Do you think it is an advantage to be the author of the book you are translating, or a hindrance?

It was very difficult to translate my own book into English. Firstly, well, you’re not supposed to do that – normally, you translate into your native language, not the other way around. However, since I’d already written books directly in English, I’m not sure that rule applies… and yet it genuinely was perhaps more difficult than writing directly in English, or than translating Sarah’s books!

I think the problem is that, when you write in one language, that language isn’t just a tool, a transparent set of words to convey an idea. It isn’t just form; it’s content, too. I couldn’t have written that directly in English; I simply don’t write like that in English normally. So translating it, I had to adapt my own way of writing (pretty naturally) in one language, into the other… where it wasn’t natural for me to write like that.

Translating Sarah’s book was paradoxically easier, because the ‘game of the translation’, in the basic sense, I kind of get. It was tricky, frustrating at times, but it made sense as a literary endeavour. For Piglettes, I sometimes got into complete brainfreeze. I was never sure whether I was rewriting, adapting, or translating.

But of course all those things are never fully separate…

Are there any elements of the book where you felt really stuck, particularly cultural references? How difficult is to balance being true to the original and ‘domesticating’ it enough for British audiences to relate? (For example you kept the name of the primary school despite no one knowing who Laurent Gerra is here)

You know, it’s funny because the editor encouraged me to keep many of the original references, including Laurent Gerra (who’s a comedian from Bourg-en-Bresse, by the way), and more prominently Indochine, a superfamous French band who’s virtually unknown here. But the interesting thing with those two references is that they’re actually unlikely to be known to the younger generation of readers… So leaving them wasn’t too much of a problem.

More generally, Daniel, my editor at Pushkin, said that I shouldn’t try to mask the Frenchness of the book – that it’s kind of the whole point. And personally I’m very interested in how translated works call attention to their being translated, if that makes sense. A translation doesn’t read like a book in the source language – and nor should it. When I translate, I try, wilfully, to leave sentences, vocabulary, turns of phrase that sound a bit off in the target language, because that’s a way of saying: this book isn’t from here, it’s written differently, it was thought up differently.

To give readers some cultural context, this is Indochine, singing 3 nuits par semaine on French TV in 1986 (Some of us are old enough to remember this …):

You are in a very unusual position that you write children’s fiction both in English and in French, different books for very different audiences. You write for all audiences in French, including the ‘middle grade’ audience which The Royal Babysitters, your series in English, is aimed at. Apart from the linguistic side of it, how different is to write for two culturally different audiences?

I don’t really write in English anymore, but I would say the most striking thing I found when I did was that it simply wasn’t the same kind of ideas that came to my head. My Sesame Seade series with Bloomsbury, for instance, would not have ‘come’ in French. The idea was moulded by my British life. It came with its own weaponry of words, conveying that super ironic politeness of British people, their wackiness, the obsession with class, the deadpan humour.

Piglettes, meanwhile, ‘came’ in French because it had so much terroir in it – terroir is an untranslatable which means all the regional/ provincial ethos, food and artisanship in France. It would have been unimaginable to make it up in English.

So I wouldn’t say I adapted to culturally different audiences, but rather that my culturally different experiences converted into text differently.

Piglettes is far from your first book in French (as seen above), though it has been a huge success, winning several prizes (including the prestigious Prix Sorcières and Best children’s book from magazine Lire), as well as the film rights being sold to Lionceau Film, and a theatre production having just finished touring. Did you think it would be the one that would get the interest of publishers here?

I was dearly hoping it would, and so it was a huge joy for me when Pushkin told me they’d take it. I think that, while there’s a very culturally-specific setting, it’s a story that had enough universal elements of YA – humour, friendship, love, existential questions, food – to work also in other countries. I take it as a real victory, too, that a book that’s not about Paris or a non-specific space (like fantasy) is making it to Britain…

I was really delighted that Piglettes was released in the UK because it is a great example of French YA. The market there is very prolific, yet so few make it across the channel. If you could bring five French YA books to the British market, what would they be, and why?

First one is very easy: Miss Charity, by Marie-Aude Murail. It’s an absolutely delightful fictional biography of someone very like Beatrix Potter. It all takes place in Britain, but it carries the double literary history of classic British stories and of early French children’s literature. It’s a joyful hybrid of Austen-style biting wit and Comtesse de Ségur-style dialogues (the Comtesse was a 19th century children’s author, still widely read today.)

Then I would translate Claudine Desmarteaux’s Jan, which would be a total tour-de-force because it’s written in Holden-Caulfield-type speech the whole time, about a kid running away from home.

Then I would translate Cécile Roumiguière’s Lily, which takes place during the war in Algeria; Annelise Heurtier’s Refuges, a delicate story which takes place on Lampedusa; and Charlotte Bousquet’s Là où tombent les anges (Where the angels fall), a fabulous feminist fresco of the home front during World War One. There are lots of other books I love, but I feel those are particularly important books in the current ‘golden age’ of YA literature in France, because they’ve got such modernity, literary strength and historical significance.

I will admit to having only read Miss Charity, but it is one of my most favourite reads ever (so much so I wrote an essay about it). So I think Lily (because I have never read anything taking place during the war of Algeria and I have several family members who fought in it, as well as a uncle who would have been identified as “pied-noir”) and Là où tombent les anges (as I am a big fan of Charlotte Bousquet’s graphic novels) might make their way onto my summer TBR list!

Thinking of the few who have made it across the channel, is there one you would recommend everybody read (apart from Piglettes, of course!)?

My instinctive answer would be Timothée de Fombelle’s The Book of Pearl, translated by Sarah Ardizzone. Timothée de Fombelle is one of France’s most important children’s writers today, and he’s a stupendous storyteller with a wonderfully poetic imagination. More generally, I think anything Sarah Ardizzone translates is likely to be fantastic.

My instinctive answer would be Timothée de Fombelle’s The Book of Pearl, translated by Sarah Ardizzone. Timothée de Fombelle is one of France’s most important children’s writers today, and he’s a stupendous storyteller with a wonderfully poetic imagination. More generally, I think anything Sarah Ardizzone translates is likely to be fantastic.

A fabulous choice indeed; I do wish de Fombelle got more recognition in this country. His books are superb. I am looking forward to reading his adult book coming out at the end of summer!

Thank you so much for taking the time to answer these questions, Clémentine.

***

You can buy a copy of Piglettes here.

Source: review copy