Today I am delighted to kick off the blog tour for Nick Garlick’s Storm Horse, published by Chicken House

Today I am delighted to kick off the blog tour for Nick Garlick’s Storm Horse, published by Chicken House

Storm Horse tells the story of Flip, a twelve year old boy who after, after his father’s death and while his mother is missing, finds himself on a remote Dutch island where storms rage regularly. His new home is his uncle’s farm, and he needs to adapt to this new way of life, learning also to deal with the bullies. Until a bad storm brings a sinking ship and a drowning horse, and changes everything. A powerful story of unconventional friendship with a wild and unusual setting, Storm Horse will appeal to a wide readership, including fans of Michael Morpurgo.

Here is Nick Garlick reading from Storm Horse:

Nick Garlick lived, worked or went to school in just about every part of England before moving to the Netherlands in 1990. After many years working as a freelance technical writer, copywriter, editor and translator, his first two children’s stories were published by Andersen Press. He now lives with his wife in Utrecht, where he’s currently working on more children’s stories.

www.nickgarlick.com

I am delighted to welcome Nick to talk about life in British boarding schools in the 1960s:

***

Making a man of you

by Nick Garlick

A young reader recently finished Storm Horse and said she was surprised how badly Mr Mesman often treated his sons. I told her that when I was her age, back in the 1960s, such awful behaviour wasn’t surprising at all.

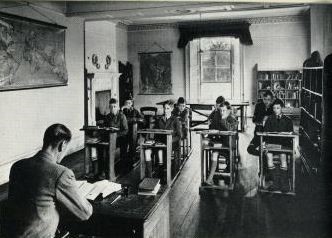

When I was eight, I told her, I was sent to a boarding school in Somerset. One day I was playing with my brother at home, the next I was surrounded by eighty boys I’d never met in my life. And with no chance of seeing any of my family for the next six weeks.

Life was bound by endless rules. Lights out at eight o’ clock at night and no talking. Brush your teeth before breakfast when you wash. Saying you brushed them after breakfast at home was met with, ‘Keep quiet and do as you’re told’. First names were out; only your last name was used. (I couldn’t even call my brother by his first name when he came to school two years later.)

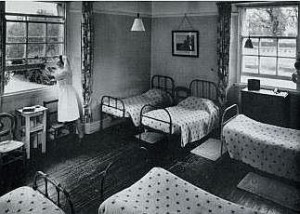

After games, no matter how wet and muddy the playing field was, all you could clean were your hands, feet and legs. We had two baths a week and twenty boys would share three baths. If you were the last in the queue, you washed in the dirty water left by all the boys before you. We slept in dormitories with six beds in one room.

And when the rules were broken we were punished. Even if it wasn’t always our fault.

One of the rules was this: No talking in the dormitories before the Wake Up bell rang in the morning. This was only a problem on Sundays, when we were allowed to stay in bed an extra hour, but woke up at the usual weekday time. So there we all were, wide awake but not allowed to do anything. That was when Robertson began talking.

Robertson always talked. Everywhere. All the time. That Sunday, other boys started talking back, telling him to be quiet – and that was when the Head of House came in. ‘Talking before the bell,’ he said. ‘See the Headmaster at breakfast. Everyone!’ So we did, and each one of us was caned six times with a piece of bamboo (By the time it reached the last boy, the end of that stalk had been smashed into splinters.) And we all missed breakfast.

Robertson didn’t learn a lesson. The next week, exactly the same thing happened again. And just like the week before, we all – whether we’d been talking or not – received six strokes of the bamboo. And missed breakfast.

This went on for six weeks. For six Sundays in a row, the Head of House came in because he heard talking. On five of those Sundays, we were all beaten. It was only on the sixth that the Headmaster finally listened to the complaints of those of us who’d never said a word. It did seem strange, he agreed, that all of us would be breaking the rule six weeks in a row. So he let us off. But Robertson, who had been talking, received eight strokes. The extra two were for getting the others in the dormitory in trouble.

Nobody ever apologised for all the unjust beatings. That was because, I said to the young reader, a lot of people thought it was quite normal to treat young boys this way in the 1960s. They thought it ‘made a man of you’. And Mr Mesman in Storm Horse wouldn’t have seen anything wrong with it for a second. He would have thought it was an excellent idea.

****

Thank you very much Nick!

Storm Horse by Nick Garlick out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)

Find out more at http://www.chickenhousebooks.com

Follow the rest of the blog tour:

Great post about boarding schools and the way boys were treated – v important. And also – what a wonderful book that sounds – I loved the reading from it = so exciting.

I agree, Anne!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?