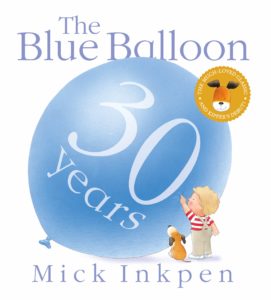

The Blue Balloon (Hodder Children’s Books), Mick Inkpen’s classic picture book, is 30 years old this year! A favourite of so many families, which uses innovative use of flaps and fold-out pages, it is a true celebration of the importance of play and the power of the imagination for preschoolers. It also highlights how easily it is for children to enter imaginative play; here a discarded balloon found by (the then-not-yet-famous) Kipper in the garden becomes the starting point of endless games and wonders.

This was written in pre-smartphone/tablet era, and it is timely reminder as to what children’s play looked like then, what it should still really look like now and how we, as adults, should nurture those opportunities.

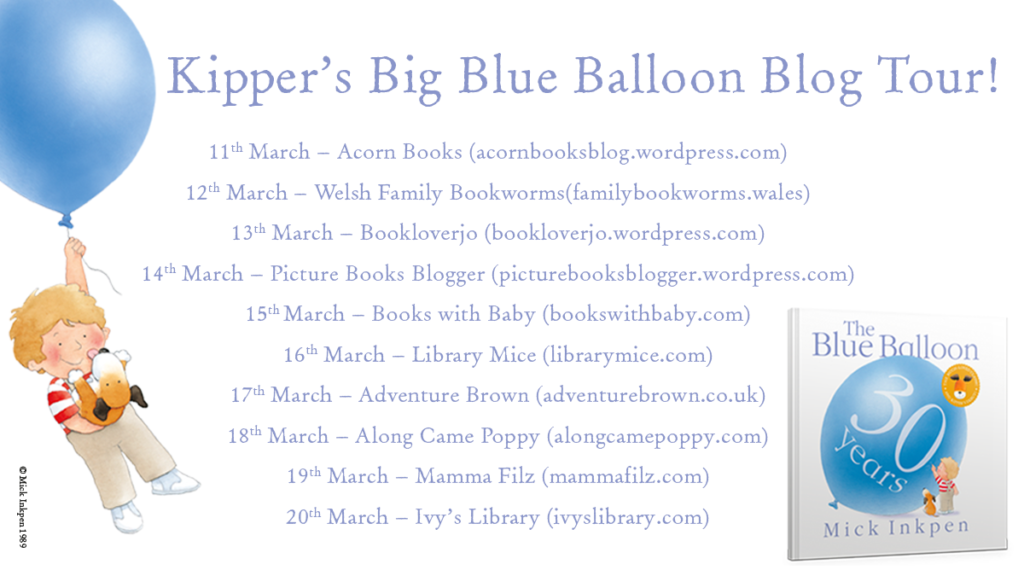

I am delighted to welcome Mick to Library Mice as part of the Anniversary blog tour, and he has written an inspiring piece about how The Blue Balloon came to life and the importance of picture books as play rather than purely pedagogical tools.

Picture Books as Playground

by Mick Inkpen

When you are four, if you have been prudent and chosen your parents wisely, life can stream at you as it is, and you in turn can run at it headlong. It’s a very singular time, where imagination co-exists happily with reality. It’s a pleasure, and I guess a responsibility, though it doesn’t feel like one,to make stories for a readership that has so little trouble suspending its disbelief.

Stories are ways of making sense of the world, ways of finding patterns and shape and resolution, ways of reaffirming meaning. Perhaps it was a growing awareness of our own unpredictable mortality that brought them into being in the first place; happy endings we can be sure of.

At any rate the need for stories is hard-wired into us. There is no issue about getting children to engage with them. Stick a child in front of the TV and they will always want to know what happened next. Reading on the other hand is a strange skill, often difficult to learn.

If we belong to that lucky group of children who learnt to read very young, we probably don’t remember the point at which those strange marks on a page began to translate into meaning. We take for granted what an astonishing lifetime of opportunity opened up for us at that point.

Unlike watching TV, reading is a much more collaborative act of imagining. How many people have read The BFG? Whatever the answer, that is the exact number of Big Friendly Giants, all of them slightly different, bought into being by the imaginations of all those readers in collaboration with the wonderful Mr Dahl. It’s this shared ownership of the story that makes reading so peculiarly rewarding.

This is an end in itself but I’m guessing that the work involved in imagining during reading is also an important component in equipping the brain to make the kind of leaps that accelerate other kinds of learning.

But teaching children to read can be tricky. Parental anxiety about it translates to kids as, ‘I must knuckle down and do this because it will be good for me’, which has very little to do with the simple pleasure of finding out what happened next. We know that children who master reading soon discover the pleasure of diving into a book independently of adults, so how do we avoid conditioning others into suspecting that books are a kind of unpleasant educational medicine?

And what is my role as a picture book author in helping children to learn to read? Well perversely I am at my most useful when I ignore that responsibility. My job is imparting stories not literacy.

When I started writing for children I felt that in order to create the kind of stories that would engage them I would need to be as playful as possible. I would need to trust my own instincts. And the key to that was being willing to entertain my own inner 4 year old self.

The Blue Balloon was not the earliest expression of that approach for me, but 30 years ago it was the most ambitious. The freedom to play extended to the physical format of the book itself. If my balloon was to have ‘strange and wonderful powers’ might it be possible for it to escape the constriction of the page? That prompted the idea of the fold out pages, and that in turn opened up new possibilities which fed back into the story. It led for example to the dramatic irony of the ending.

As the child reading the story opens out the final double folding page, the boy narrator is unaware that behind him the blue balloon is elongating into rainbow colours. At that point the child reading becomes the sole custodian of the facts. For a four year old that is pretty empowering. Over the past thirty years I’ve often tried to subvert roles to the advantage of my reader.

The point is that none of this was carefully rationalised. It arose spontaneously out of a willingness to be playful. The ideas and text for The Blue Balloon seemed to unpack themselves in the course of one afternoon. Not all picture books are so cooperative, but that afternoon set a marker early in my career. It taught me the importance of playfulness and gave me the confidence to pursue it in my work.

Picture books at their best are an affirmation of this quality. They don’t set out primarily to educate or improve, they simply celebrate all the possibilities of being three or four or five years old.

***

Thank so much for this amazing piece, Mick! So much food for thought.

The Blue Balloon’s 30th Anniversary edition is out now and can be purchased here.

Don’t forget to check out the other stops of the blog tour:

Source: review copy kindly sent from publisher

Kipper was so well loved by my grandaughter I had to make her a Kipper birthday cake when she was three. Wonderful illustrations, Mick. Thank you.

That sounds like an amazing cake 🙂

Love The Blue Balloon (well, Kipper and Mick Inkpen’s books in general!) and this was a really interesting read. I love reading about how authors work etc. – the analogy about all the slightly different BFGs is a wonderful thought.

I am glad you enjoyed it!